Trauma… A contemporary French play, False Note, about trauma, retribution, and resolution in Ukrainian with English surtitles comes to London from war-ravaged Ukraine for one night only. Remarkable. It is difficult to review the play in the context of the present pointless war raged by a demented egomaniac with a deranged narrative. We have seen plenty of this on our screens during the last nine months.

It’s a hard watch revisiting WW2 war crimes, it always is. Kyiv, where the company is based, is feeling them on its skin right now. Ukraine has a history of being on the receiving end of Russian and German megalomania: Stalin’s famine, Hitler’s occupation, Tsarist banning of the Ukrainian language. And here we are again. How much more can a nation and its people take?

Watch Adam Curtis’s TraumaZone Russia 1985–1999 and maybe Russia’s mindset, incompetence and barbaric indifference to its apathetic people will come some way to explaining the incomprehensible. A big-eyed little boy tells of stepping over dead bodies. He will be traumatised forever and no doubt will hand it down.

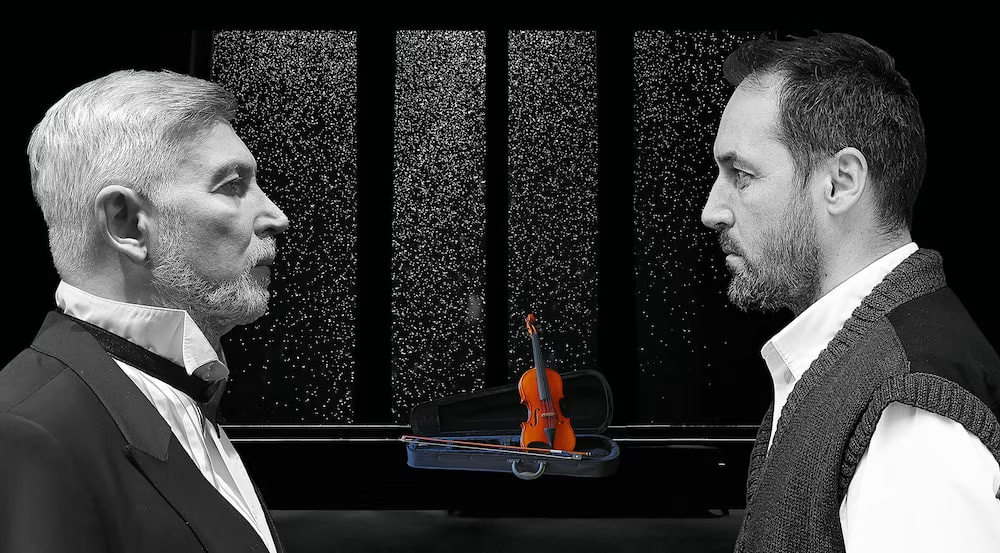

This is the essence of False Note. A two-hander essentially brings to life the Nazi past in a concentration camp, in Auschwitz, a cat and mouse game that reminds me a little of Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth.

It starts like a comedy: an annoying creepy fan, Dinkel, gets into the Geneva dressing room of famous conductor Miller. Dinkel brings bouquet after bouquet of flowers, wants an autograph for his wife, then a photo, then a feel of the violin, then for Miller to play it. Miller can’t get rid of him. He goes and comes back ad nauseam. It stops being funny. Something is afoot. There’s a present for Miller in a bag to be opened later…

This is absurd and sinister. Who said comedy is tragedy plus time? Well, this is no comedy unless you see all of life as a black farce. Dinkel has gained entrance, confuses his target, locks the door and disconnects the phone. He has Miller where he wants him. He has found the man he has been looking for since that time in the camp, the time Miller as a young soldier shot Dinkel’s violinist father.

Miller’s father the camp commandant ordered him to do it. Dinkel’s emaciated father was playing in a band at the gates in the snow with frozen fingers and hits the wrong note. “Mozart ist mein Gott,” the Nazi says. Reason enough it seems. His son must do it, hand supporting trembling hand. He still has this idiosyncrasy when picking up the bow. This is how Dinkel spotted him, though he has collected plenty of incriminating evidence to counteract Miller’s denials.

Miller (real name Keitel) is at the height of his career, about to take over as head of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from Herbert von Karajan. Now here’s a thing—Karajan was a member of the Nazi party. Many throwaway lines bring up monsters from the deep. Many Nazis melted back into the woodwork after the war, and many had successful careers.

Finally, Miller confesses. To cut a story short, Dinkel wants him to play the violin and if he plays the wrong note… He leaves the gun for him to play the ancient Roman. But after pulling the trigger several times, Miller finds the gun is not loaded. Dinkel wants retribution, for him to know how it feels. His father, a spiritual man, a rabbi maybe, would not have wanted a death on his head.

It’s about fathers and sons. Philip Larkin’s “Man hands on misery to man. / It deepens like a coastal shelf” comes to mind. Miller loved his Nazi father and he him, and yet… Dinkel loved his father, a gentle soul it seems. So is Dinkel. How much of our parent’s nature and nurture disfigure our lives? Both fathers loved Mozart; Dinkel prefers Vivaldi. Music will save us, his father said…

How many plays about that war have we seen? And films? We can’t get enough of them. C P Taylor’s Good (how a good man becomes a Nazi) is playing in town, and next month, Lillian Hellman’s Watch on the Rhine opens at the Donmar. But this one resonates for Ukraine, a traumatised nation for decades to come. And so the wheel of history turns.

A contemporary play Fausse Note, written 2017 by French actor / writer Didier Caron, has been translated into many languages, played in Israel, at Festival Avignon le Off with Pierre Azéma as H P Muller (sic) and Pierre Deny as Léon Dinkel. I’d never heard of it. I do some research and find not only does Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theatre have it in its repertoire but that Cheshire’s The Harlequin Players Club amateur theatre is planning to do it next year under a new title, The Conductor. It is Caron’s tenth play.

A production by Mikhail Reznikovich, directed by Kirill Kashlikov, False Note is recommended for 16+—and I wonder about the children in Ukraine with no age limit to the present horror. It plays ninety minutes with no interval: tension builds. Dmytro Savchenko dominates as Dinkel, whilst Oleh Zamiatin’s Miller is a worthy guilty foil. Nazi Keitel-father (Oleh Savkin), his son (Andriy Kovalenko) and Dinkel’s father (Serhii Detiuk) complete the cast, chosen no doubt for their physical looks.

The company has had to borrow set and scenery (set design and costumes Elena Drobna), as they were only able to bring a small crew, many doubling and tripling behind the scenes. The video back-projection is falling snow against a black sky (video support Oleksii Rabin, Andrii Ryabin, Oleksandr Shabanov). Lighting design is by Anatoly Burov. Music by Oleksandr Shymko and sound design by Alla Muravskа are almost accusatory. How can music serve such evil men?

UCL’s Logan Hall seats 920… will it be full, who will come to it? The Ukrainian diaspora, of course, almost fills it. I’d like to have seen False Note in a more intimate space like the Donmar or the Royal Court. The last time the company came with four plays to London was in 2015 to St James Theatre. But kudos to them for making that arduous journey…

Reviewer: Vera Liber