Linbury Prize-winning Sami Fendall’s black sandpit set is an excellent locale for this transposition of Strindberg’s misogynistic Miss Julie to a 2012 New York City, BDSM party. What at first looks like a weird playground for Julie and John’s tense flirting becomes a sinister wrestling ring in which they throw each other against the ropes, bouncing back for more.

Rather like wrestling, the interaction between privileged college girl Julie and her father’s intern, the older John, appears staged and artificial but nonetheless serves to establish a distribution of power.

That distribution seesaws like a pump handle ramping up the friction, and the sense of uncertainty is maintained as their focus is drawn to the S&M roleplaying they are, by definition, at the party to engage in.

Writer Kim Davies’s intricate, not un-funny, reworking of the 1888 classic bigs up the sexual frisson of the original and skilfully blurs the boundary between the power one has over the other as predetermined by society and the erotic power exchange of the BDSM setting.

Whilst status, age, gender and wealth define their roles and limitations in one respect, in the sexual role-playing where Julie is the novice and John, by virtue of his experience, is her guide, that is thrown aside and we see the selective lowering of guards as history is shared, desires are revealed and boundaries are identified.

There is something anonymous and calculating about this negotiated thrill-giving and by today’s standards there is too little said about abuse of power or consent, but the sub hitting back against the dom outside of the playground gives an interesting edge.

Co-directors’ Júlia Levai and Polina Kalinina’s production uses the black sand as both prop and language. John and Julie exchange it, play with it casually, demonstrate with it sensually, get dirty with it and throw it to indicate violence.

It is effective enough in a play that would be unstageable without such an intermediary device, but it has its flaws. When John pours sand over a recumbent Julie in a representation of knife foreplay, it looks weird rather than uneasily sexual or threatening, and when there is physical contact, I was left wondering what I had missed that it was not representational.

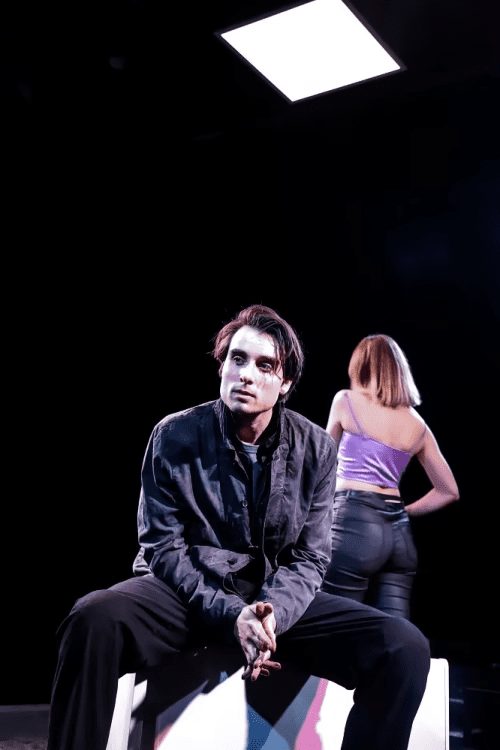

This does not detract from the two assured and immensely watchable performances. Oli Higginson plays a vulnerable intern and sexually confident John with ease, but Meaghan Martin’s Julie holds her own cards. Her performance walks a subtle line between wanting “to be broken” and knowing where she has the upper hand.

Southwark Playhouse’s Little makes the intensity and occasional discomfort of this play inescapable. Levai and Kalinina’s direction in-the-round magnifies the game of chase between Julie and John, and the difficult intimacy when they come together around the upturned fridge that nods to their kitchen encounter.

When a production is in-the-round, some of the audience will always miss out and with the closing scene of Smoke it was my turn. Not seeing the final tableau has left me without a sense of closure, even if I do have lots to think about. A large part of me is holding out the hope that Davies broke away from the original and has Julie playing the game right to the end.

Reviewer: Sandra Giorgetti