J B Priestley (1894–1984) was a prolific writer of novels, short stories, essays, plays and passionate left-wing polemic. He was an influential figure during and after WW2, an enthusiastic supporter of Attlee’s postwar socialist government and co-founder with Bertrand Russell and others of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

An Inspector Calls provided Priestley with an opportunity to express his views on social inequality in Britain, the class divide, unchecked capitalism and “the exploita-tative tendencies of the “haves”‘ in contrast to “the despair, resentment and lack of opportunities of the “have-nots”‘ (programme note).

In the early stages of an increasingly distinguished career, director Stephen Daldry teamed up with talented designer Ian MacNeil to revolutionise what some might see as a theatrical pot-boiler firmly embedded in the Edwardian era and transform it into a play with lasting and universal significance. This was the play he chose for his debut production at the National Theatre in 1992. Over 30 years later, it is still intriguing audiences. A ‘whodunnit’ with a difference.

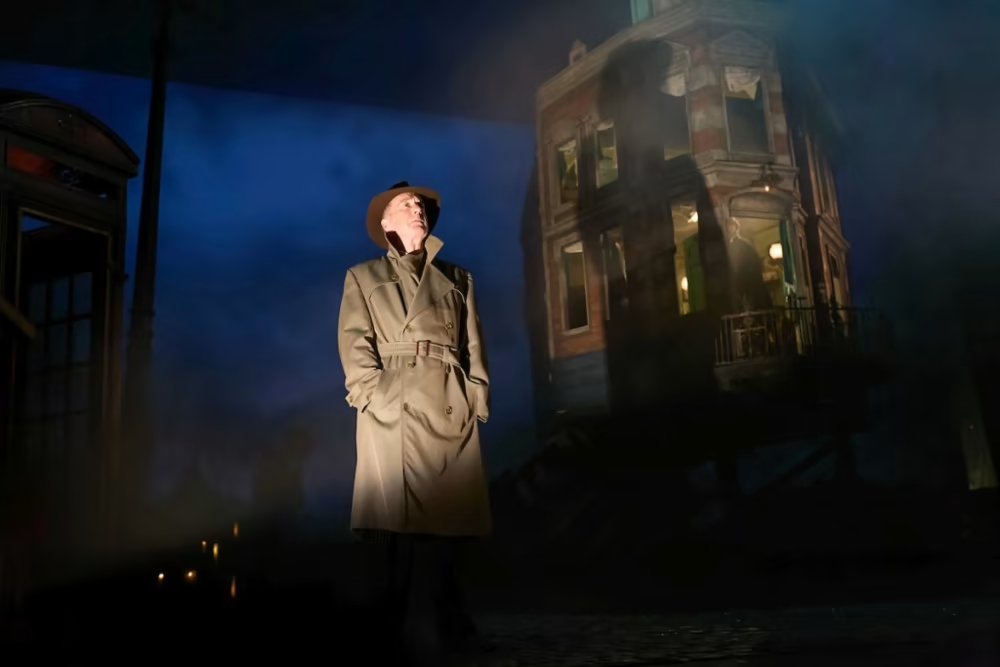

There are two transforming concepts in the production: the first is to present the cosy, wealthy Edwardian home of the Birling family as a metaphor for society; and the other is to frame the action set in 1910 with an external context set in the rubble of war damaged Britain in the 1940s. So, there is a dissonance between the elegantly dressed family party and the shadowy, silent, hungry group of watchers in the surrounding war-damaged street. The greyness and dirt of the watchers gradually impinges on the advantaged group, as the sordidness of their complicity in the death of the young factory worker is gradually revealed.

The Inspector, played by Liam Brennan, is an ambiguous, all-knowing Teiresias figure more than a policeman, with a mission to draw out confessions from the family and to stir their consciences. He is only partially successful in this, as the older, establishment members of the family are hard to reach. The play ends with a mystery and a sense that time and revelations will be repeated.

This is a well constructed and lucidly written play, in the best tradition of the ‘well made’ play stretching back to Ibsen. There are assured and convincingly characterised performances from the whole cast. The older generation of establishment figures, played by Christine Cavanagh as Sybil Birling, Jeffrey Harmer as her husband Arthur and Simon Cotton as Gerald Croft, assert the values they have always lived by and are untouched by any suggestion that they should take responsibility for their actions. Their instinct is to discredit the Inspector and use their influence to cover things up.

Son Eric, played by George Rowlands, is finally overwhelmed by remorse, and Chloe Orrock as daughter Sheila Birling, initially a charming and elegant butterfly, recognises the part her self-centred petulance has played in the tragedy, regrets her action and looks as if she might be capable of change.

The small army of silent watchers, including the younger boy, Leonard Bailey, who is a constant presence in the action, fulfil a crucial function in reminding the audience that there is a community of disadvantaged people out there who are deeply affected by social inequality.

But the real star of this show is the brilliant set, which metaphorically opens up to reveal the secrets and lies which are hidden behind the opulent façade, and gradually degenerates and implodes as the protected world of exploitative capitalism is seen to disintegrate.

The current revival is more melodramatic and unrestrained than the original, but was well received by a full audience of GCSE students studying the play for their exams. An unfortunate slip on the steep curving metal staircase led to a short delay, but in grand theatrical tradition, action was bravely resumed, hopefully without serious injury to the actors concerned.

Reviewer: Velda Harris