At least a hundred Internets ago, Samuel Johnson famously wrote: “he who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.” But Eleanor Hill’s savage exploration of self-loathing in the Instagram age shows that the same is true now as then for anyone, regardless of gender.

So what does a modern woman, caught in the throngs of mental illness, toxic relationships and the hyper-performativity of the modern age, do to forget the pain of living? Eleanor Hill gives us an answer in the form of a twisting tale of modern online bare-all social media oversharing. It’s as if Bo Burnham’s Inside was made by Bridget Jones’s drug-addled cousin.

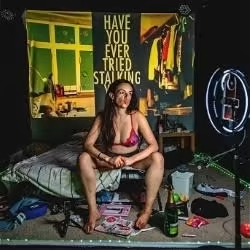

Looking almost like a mockery of Tracey Emin’s My Bed, the stage shows the squalor and mess of Eleanor’s life as she drowns herself in cheap alcohol and prescription drugs as well as illicit substances. Through this, we hear about her mental health and self-sabotaging relationship dramas, as well as her long held traumas and some unsettling moments of sexual abuse.

It’s a great premise and a cuttingly dark and grimily raw performance, as the story winds its way through various titled chapters. The gimmick of the piece is that the entirety of the show is narrated, not to the audience, but rather to a phone and live-streamed onto the stage wall, complete with a half-second time-lag.

This always-online, constantly streaming aspect of the show is also smartly modern and thematically on-point. But it is let down slightly by the subterranean Underbelly venue not having great reception, or an audience accessible Wi-Fi signal (a curious omission). Thus the show touting itself as being live-streamable and actively encouraging phone use and live-tweeting and Instagramming throughout falls a little flat. Theoretically, Hill is open to replying to live messages during the piece to improvise or respond; although this never occurred during the performance I saw, possibly again due to lack of reception, though one comment that the stage “must be a nightmare to tidy up” flashed up momentarily and was roundly ignored.

This is a minor quibble and a site-specific issue, but it doesn’t take away from Hill’s honest performance of over-honest performativity. Rather, this abbreviated tale of self-loathing and self-destruction ends up being painfully real, both in the sorrowful mundane horror of her too-realistic abuse, as well as the fixed-grin, Instagram-filtered performance of the self-mocking personality on display.

It’s a devastating enacting of the truly believable pain of modern life, filtered, edited and wrapped up in emoji, practically begging to be liked and followed. This critic at least will be following all involved with great interest.

Reviewer: Graeme Strachan