Review by Ellen Murray

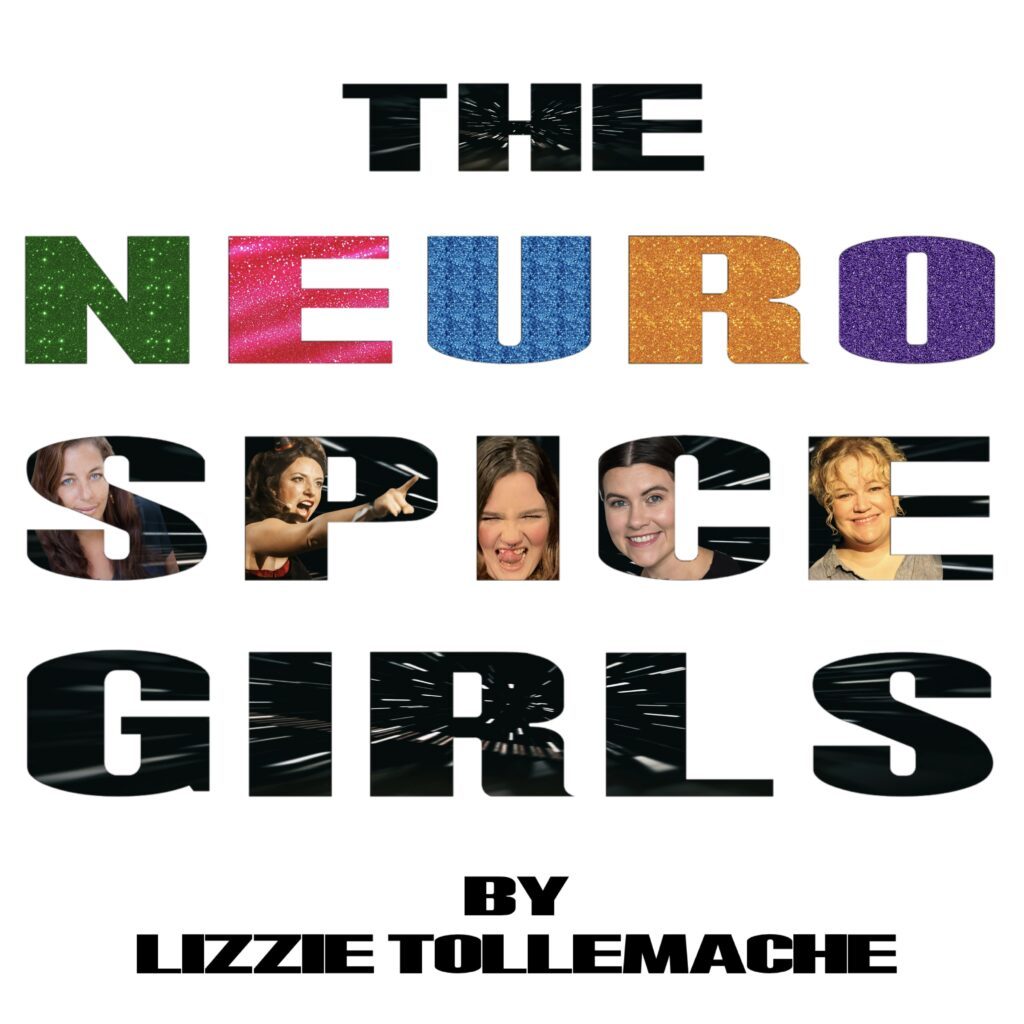

The Neurospice Girls, written by and starring the dynamic Lizzie Tollemache, braves complex issues with humour and heart but not always enough clarity.

The show premiered to a full house, an engaged audience laughing and murmuring affirmatively throughout. A Greek chorus supports Tollemache, featuring Mārama Grant, Lexie Tomlinson, Ellie Swann, and Destiny Carvell. Kim Morgan directs, with Matthew Morgan, Garry Keirle, Sahara Pohatu-Trow, Jordan Wichman, Milla Swanson-Dobbs, and Courtney Drummond bringing their talents to the production’s design and crew.

The title and marketing are a bit misleading. This is firmly a one-woman show, and that’s where it’s at its best: when Tollemache focuses on her specific experiences rather than extrapolating them into universal representations of neurodivergent girlhood. This is a difficult review to write because The Neurospice Girls was surely a difficult show to write, with its complicated and personal themes. Above all, artists should be commended for the risks they take in making bold, vulnerable work, even when there is room for growth.

For those unfamiliar, the term “neurospicy” is internet parlance for “neurodivergent,” which originated in the 1990s to de-emphasize deficits and pathology and instead embrace differences in how people think about and experience the world. While some people find the “neurospicy” moniker to be affirming and depathologizing, others find it sanitizes the complex, lived experiences of disability.

As neurodivergency—and its neologism neurospicy—become more popular terms, especially online, their meanings have become increasingly vague, referring to a range of significantly different conditions from autism to depression to traumatic brain injuries. This lack of specificity hinders the communication of people’s unique contexts and needs, and this lack of specificity plagues Tollemache’s play.

Throughout the almost ninety-minute production, Tollemache and her externalized Greek chorus repeat the same refrain, asking: “Who are you?” The same can be asked about the play itself—is this a play about autism? ADHD? Trauma? That is not to say that the play cannot be about multiple things or that they don’t overlap. Research suggests that autistic people are more likely to experience PTSD than the general population, estimating that 32–45% of autistic people report symptoms compared to around 4% of the general population. However, these conditions are distinct, with different treatments, comorbidities, and lived experiences, so collapsing them under one umbrella risks integral nuance.

Dr. Nick Walker positions neurodiversity as a paradigm shift away from the pathological assumptions that there is a “normal” way for human brains to function. The Neurospice Girls remains stuck in this pathological paradigm, focused on difference, and, for that reason, is much more a play about trauma than neurodivergence. While these concepts are related, Tollemache doesn’t separate them sufficiently.

Primarily, the production seems to want to educate its audience. Informational posters for podcasts, books, and online questionnaires about trauma, autism, and ADHD filled the lobby. Before, during, and after the show, Tollemache guided the audience to these resources. These production choices were very well-intentioned. It was clear the creative team had sincere and genuine care for everyone’s wellbeing, but this educational emphasis becomes more questionable in the context of the show’s lack of specificity.

The performance’s denouement gestures toward an overarching theme of acceptance. Tollemache’s struggles have not been fully resolved, nor can they be, but she has found the self-knowledge and community she needs to continue onward. The end of the performance features a curtain call of sorts, each member of the Greek chorus stepping out of their role to share their personal history, including experiences of significant trauma.

Before this, the Greek chorus’s role has been somewhat ancillary. They are a solid dramaturgical device, adding dynamic physicality and colour and helping externalize Tollemache’s internal struggles, but it is always clear that this story is hers. So, it was jarring for these other actors to introduce their personal traumas suddenly, especially at the end of the performance. Post-show rituals play an essential role in helping artists and audiences process what they’ve experienced and transition away from the performance and back into the real world, so to speak. As a result, using them as a device can backfire.

UK arts organization Collective Encounters distinguishes between creative and therapeutic outcomes in their training on trauma-informed artistic practice. At times, The Neurospice Girls felt like it intended therapeutic outcomes, for the performers or audience, but without the boundaries or professional support necessary for the level of disclosure that the show solicits from its actors and potentially audience.

The opening night audience was effusive in their reactions, and I have no doubt that many people will enjoy this production and even see themselves reflected in the performance, but I’m not sure that the reflection is totally clear yet. Given the show’s complex, sensitive topics, it would benefit Tollemache to continue clarifying her core ideas: What is the story about? What does she want from her audience? And how can she best support her collaborators and audience toward a meaningful, even revelatory experience as they navigate these topics with her.

Copyright © in the review belongs to the reviewer